Emotional intelligence isn’t just a buzzword—it’s the invisible force that determines whether you thrive in your relationships, excel as a leader, or crumble under pressure. While your IQ might get you hired, your EQ determines how far you’ll actually go.

This comprehensive guide explores everything you need to know about emotional intelligence: what it is, why it matters more than traditional intelligence in most life situations, how the brain learns these skills, and most importantly—how you can systematically develop your own EQ starting today.

What Defines Emotional Intelligence (EI or EQ)?

The Essential Definition: Emotions as Data for Decision-Making

Emotional intelligence is the ability to perceive, use, understand, and manage emotions—both your own and those of others. Think of emotions as a sophisticated information system: they provide crucial data about what matters to you, what’s changing in your environment, and how others are responding to you.

When you possess high emotional intelligence, you don’t suppress or ignore feelings. Instead, you recognize them as signals, decode what they’re telling you, and use that information to guide your thinking and behavior effectively.

The term “emotional intelligence” was formally introduced by psychologists Peter Salovey and John Mayer in 1990, but it exploded into mainstream consciousness through Daniel Goleman’s 1995 bestselling book. Goleman, a science journalist covering behavioral and brain sciences for The New York Times, synthesized decades of research to show that EQ matters as much—if not more—than IQ for success in life.

Want to assess where you currently stand? Take our free emotional intelligence test to discover your strengths and development areas.

EI vs. IQ: Why Emotional Quotient Predicts Excellence

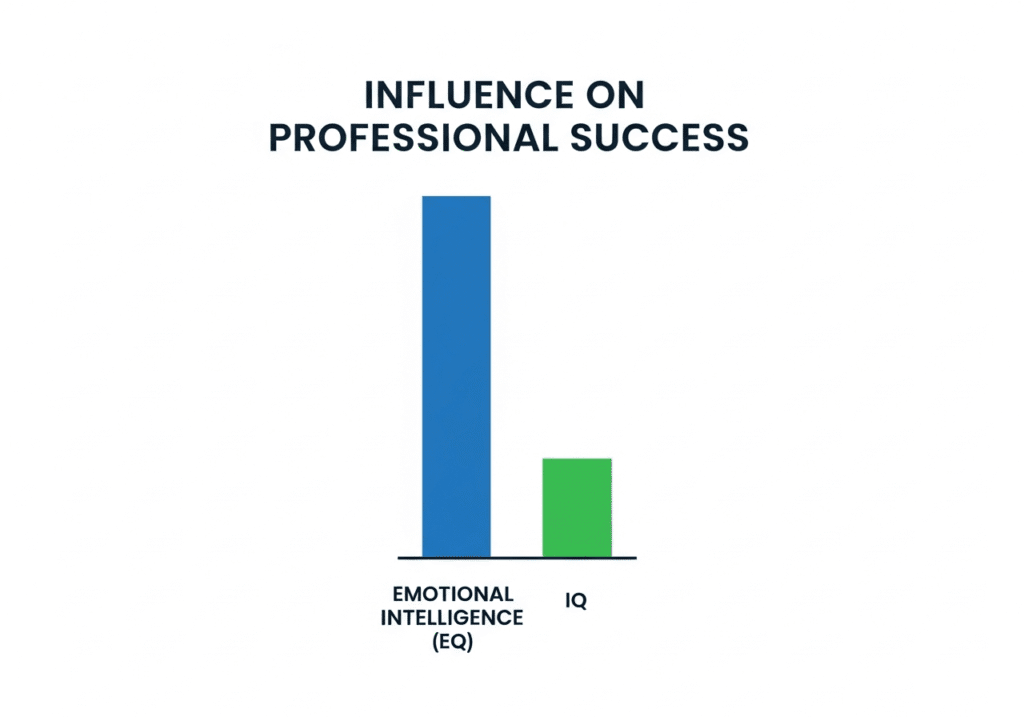

Here’s the paradigm shift that changed how we think about success: IQ gets you in the door, but EQ determines whether you become exceptional at what you do.

Traditional intelligence (IQ) measures cognitive abilities—logical reasoning, mathematical skills, verbal comprehension. These matter enormously for academic success and entry-level professional competence. But research consistently shows that beyond a certain threshold (typically around 120 IQ points), cognitive intelligence alone stops predicting superior performance.

The critical difference: IQ is relatively fixed after adolescence. You’re essentially stuck with the cognitive capacity you have. Emotional intelligence, by contrast, is highly learnable throughout your entire lifespan. Your brain’s neuroplasticity—its ability to form new neural pathways—means you can systematically strengthen your emotional skills at any age.

Studies of executives, leaders, and high performers across industries reveal a striking pattern: the competencies that distinguish outstanding performers from average ones are predominantly emotional and social skills, not technical or cognitive ones. As Goleman’s research demonstrated, roughly two-thirds of the competencies that create excellence in leadership positions are emotional intelligence abilities.

For a deeper comparison of these two forms of intelligence, explore our guide on emotional intelligence vs IQ.

A Brief History and Daniel Goleman’s Role in Popularization

While Goleman brought emotional intelligence into public awareness, the concept has deeper roots. Psychologists have long recognized that success requires more than traditional “book smarts.” In the 1940s, David Wechsler (creator of the Wechsler IQ tests) noted that “non-intellective” factors were essential for success in life.

The modern framework emerged through the work of Salovey and Mayer, who in 1990 defined emotional intelligence as “a form of social intelligence that involves the ability to monitor one’s own and others’ feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them, and to use this information to guide one’s thinking and action.”

Goleman’s 1995 book “Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ” transformed the field by making the research accessible and showing its applications across education, workplace performance, and personal relationships. His work drew on neuroscience discoveries about the emotional brain, particularly the amygdala’s role in emotional responses and how the prefrontal cortex can regulate those responses.

Today, emotional intelligence training has become standard in progressive organizations worldwide, from Fortune 500 companies to military special forces units.

Models and Frameworks of EI: The Three Main Approaches

Understanding emotional intelligence requires recognizing that multiple valid frameworks exist. Each emphasizes different aspects of how we recognize and work with emotions.

The Mixed Model of Daniel Goleman (The 4 Domains)

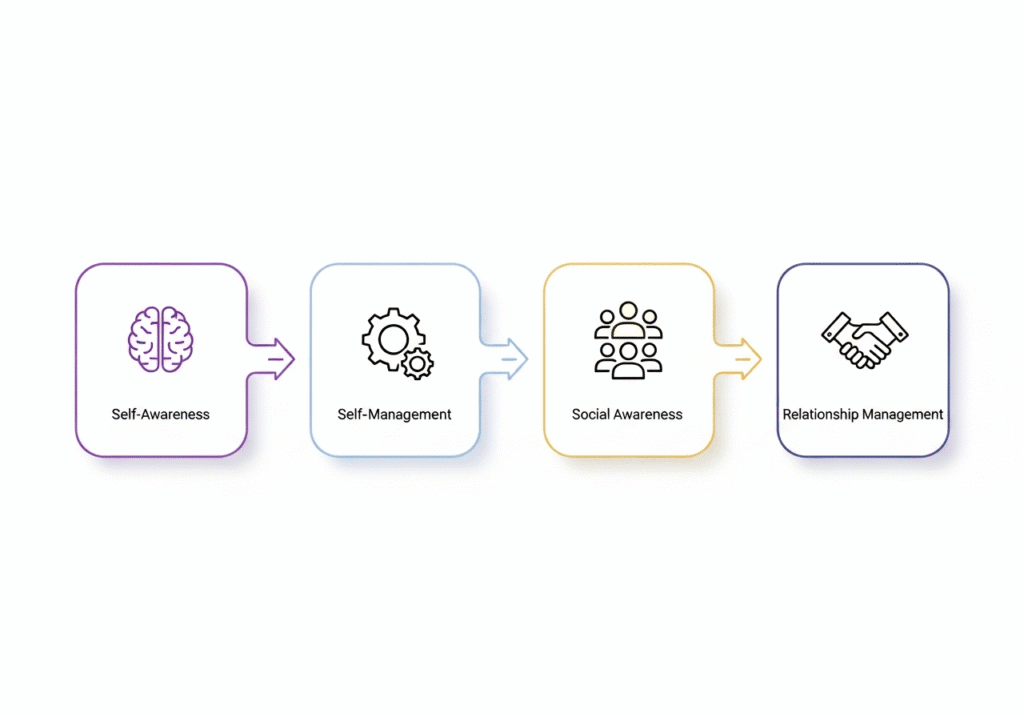

Goleman’s framework is the most widely recognized and practically applied model. He organizes emotional intelligence into four core domains that span both internal skills (working with your own emotions) and external skills (working with others’ emotions). Let’s explore each of these components of emotional intelligence:

1. Self-Awareness: Knowing What You Feel

Self-awareness is the foundational competency—everything else builds upon it. It means having a clear, accurate understanding of your emotions as they occur, recognizing how they affect your thoughts and behavior, and understanding your strengths and limitations with genuine self-confidence.

People with strong self-awareness can identify subtle emotional shifts (“I’m not just frustrated—I’m actually feeling insecure about my competence on this project”) and understand how their moods influence their perceptions (“I’m seeing everything negatively right now because I’m exhausted”).

Without self-awareness, you’re essentially flying blind—reacting unconsciously to emotional triggers without understanding why. This is why self-awareness consistently emerges as the most critical emotional intelligence skill.

2. Self-Management/Self-Regulation: Managing Impulses and Adapting

Self-management is your ability to control impulsive feelings and distressing emotions, to remain composed under pressure, and to maintain your effectiveness even when things go wrong. It includes adaptability (being flexible in handling change), achievement orientation (striving to improve or meet standards of excellence), and maintaining a positive outlook.

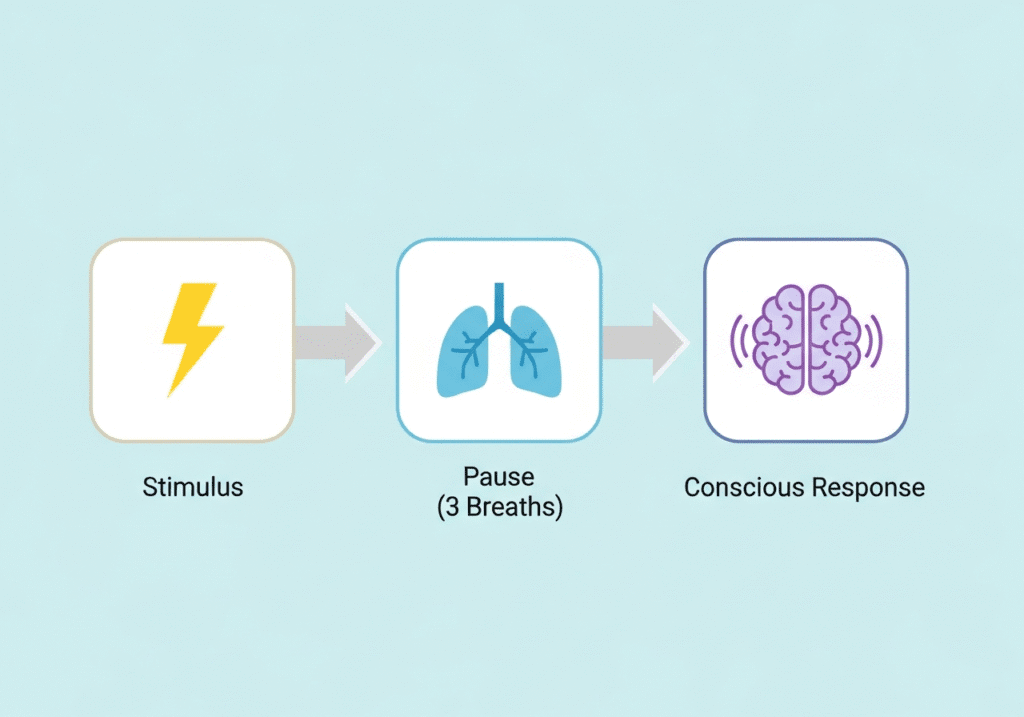

Think of the space between stimulus and response. People with weak self-management have almost no space—they react instantly to triggers. Those with strong self-management create a pause where conscious choice becomes possible.

For practical techniques to strengthen this critical skill, see our guide on emotional self-regulation techniques.

3. Social Awareness: Empathy and Attunement to Others

Social awareness means accurately reading other people’s emotions, understanding their perspectives, and being attentive to emotional currents in groups and organizations. At its core is empathy—the ability to sense what others are feeling and take their perspective.

Empathy isn’t just about being nice; it’s an essential skill for understanding what motivates people, what concerns them, and how to communicate effectively with them. Leaders with strong social awareness can read a room, sense unspoken tensions, and understand the political realities of their organization.

Learn specific methods to strengthen this crucial ability in our article on how to develop empathy skills.

4. Relationship Management: Influence, Inspiration, and Conflict Navigation

Relationship management encompasses all the skills needed to interact effectively with others: developing people, having difficult conversations, managing conflict constructively, inspiring and influencing others, and building strong collaborative relationships.

This domain represents emotional intelligence in action—taking everything you understand about your own and others’ emotions and using it to create positive outcomes in your interactions. It’s where the rubber meets the road in leadership, teamwork, and personal relationships.

For workplace-specific applications, explore our comprehensive guide on emotional intelligence in the workplace.

The Ability Model (Salovey & Mayer): The Four Branches

The original Salovey-Mayer model treats emotional intelligence as a distinct form of intelligence—an actual cognitive ability rather than a mix of skills and personality traits. Their framework consists of four branches, arranged hierarchically from basic to more complex processes:

Branch 1: Perceiving Emotions – The ability to detect and decode emotions in faces, voices, pictures, music, and other stimuli. This includes identifying your own emotions.

Branch 2: Using Emotions to Facilitate Thinking – Leveraging emotional states to enhance cognitive processes. For example, positive moods can facilitate creative thinking, while contemplative moods can support analytical reasoning.

Branch 3: Understanding Emotions – Comprehending emotional language, recognizing relationships between different emotions (how anger can stem from hurt), and grasping how emotions evolve over time.

Branch 4: Managing Emotions – The ability to regulate emotions in yourself and others to promote emotional and intellectual growth. This includes staying open to pleasant and unpleasant feelings and managing emotions to achieve goals.

The Ability Model is measured through performance-based tests like the MSCEIT (Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test), where responses are scored based on how they compare to emotion experts’ answers—similar to how an IQ test works.

For a detailed comparison of different frameworks, read our analysis of Goleman’s emotional intelligence model.

The Six Seconds Model (Know-Choose-Give): A Blueprint for Practice

Six Seconds, a non-profit organization dedicated to emotional intelligence development, offers a particularly actionable framework organized around three pursuits:

Know Yourself – Building self-awareness by recognizing patterns in your feelings and reactions. This pursuit includes enhancing emotional literacy (expanding your feeling vocabulary) and recognizing patterns (seeing the recurring themes in your emotional life).

Choose Yourself – Taking ownership of your responses rather than reacting on autopilot. This includes consequential thinking (connecting choices to outcomes), navigating emotions (assessing and harnessing feelings rather than being controlled by them), and engaging intrinsic motivation (connecting to deeper purpose).

Give Yourself – Moving beyond yourself to consider others and the larger purpose. This includes exercising empathy and pursuing noble goals—connecting your daily choices to your overarching sense of purpose.

This KCG model is particularly valuable for creating a personal development roadmap, as it clearly links abstract concepts to concrete practices.

The Power of EI in Leadership and Success (Case Studies in Action)

Theory is compelling, but real-world evidence is what makes emotional intelligence undeniable. Let’s examine how EQ manifests in actual performance across diverse contexts.

EI as the Core of Effective Leadership

Leadership is fundamentally an emotional practice. Leaders set the tone for their teams, and that tone reverberates through every interaction and decision. Research across industries consistently shows that the most effective leaders possess high emotional intelligence.

Why? Because leadership isn’t primarily about strategies, systems, or technical knowledge—it’s about influencing how people feel, which in turn drives how they think and act. Leaders with high EQ excel at several critical tasks:

- Creating psychological safety where people feel secure enough to take risks and innovate

- Providing clarity of expectations while remaining flexible when circumstances change

- Inspiring intrinsic motivation by connecting work to meaning and purpose

- Navigating conflict productively rather than avoiding it or letting it fester

- Developing others’ capabilities through feedback and coaching that actually land

Conversely, leaders with low emotional intelligence—no matter how brilliant their technical skills—create toxic environments that suppress performance. They misread situations, alienate talented people, and create cultures where fear and politics dominate.

Want to develop your leadership EQ specifically? Our guide on emotional intelligence for leaders provides targeted strategies for executive development.

Emotional Contagion: How Leader Mood Affects Team Performance

One of the most fascinating discoveries in organizational research is the phenomenon of emotional contagion—the process by which emotions spread from person to person, much like a virus.

Yale School of Management researchers demonstrated this powerfully in controlled studies. They found that within two minutes of interaction, group members’ emotions converged, and this emotional state directly predicted the group’s performance. Groups that “caught” positive emotions from their leaders showed better cooperation, less conflict, and superior task performance. Groups exposed to negative emotional tones performed significantly worse.

The mechanism is largely unconscious. We automatically mimic others’ facial expressions, vocal tones, and body language, and through this mimicry, we begin to feel what they’re feeling. Mirror neurons in our brains fire both when we experience an emotion and when we observe someone else experiencing it.

For leaders, this creates both tremendous responsibility and tremendous leverage. Your emotional state isn’t just personal—it’s organizational infrastructure. When you walk into a meeting anxious and irritable, you’re not just in a bad mood; you’re potentially degrading your team’s cognitive capacity and collaborative ability.

The most emotionally intelligent leaders understand this dynamic. They don’t fake positivity or suppress authentic feelings, but they do take responsibility for managing their emotional state before high-stakes interactions, recognizing that their mood is contagious.

To understand how emotional intelligence manifests in everyday work situations, check out our collection of emotional intelligence examples in the workplace.

Extreme Pressure Case Study: EI and Special Forces Training

Perhaps the most dramatic evidence for emotional intelligence’s impact comes from high-stakes military contexts. The Australian Special Forces conducted a revealing study on how emotional intelligence training affects performance under extreme stress.

Special forces operators face situations most of us can’t imagine: life-threatening scenarios requiring split-second decisions while managing intense fear and pressure. Traditional training focused exclusively on physical conditioning and tactical skills. But researchers wanted to test whether adding emotional intelligence training would improve performance under these extreme conditions.

They measured cortisol levels (the primary stress hormone) in operators during high-stress training scenarios before and after emotional intelligence training. The results were striking: operators who received EI training showed significantly lower cortisol responses when facing identical stressors.

Lower cortisol isn’t just about comfort—it’s about performance. When cortisol floods your system, it impairs complex decision-making, reduces cognitive flexibility, and narrows attention. The operators with better emotional intelligence weren’t less committed or less aware of danger; they simply regulated their stress response more effectively, maintaining cognitive capacity when it mattered most.

This finding has profound implications beyond military contexts. Any high-pressure environment—emergency rooms, courtrooms, corporate crisis situations—demands the ability to think clearly while experiencing intense emotions. Emotional intelligence training provides that capacity.

If you work in a particularly challenging or conflict-heavy environment, our guide on emotional intelligence conflict resolution offers specific strategies.

EI Beyond the Office: The Bus Driver Govan Brown Story

Sometimes the most powerful examples of emotional intelligence come from unexpected places. Consider Govan Brown, a bus driver whose story Daniel Goleman featured as an exemplar of EQ in action.

Brown didn’t work in a leadership role or high-status position. He drove a city bus route in a challenging neighborhood. But he understood something fundamental: his emotional state and relational skills profoundly affected everyone who stepped onto his bus.

Brown greeted every passenger personally, remembered regulars by name, and consistently maintained an atmosphere of warmth and respect. He defused potential conflicts before they escalated, made people smile during their commutes, and created a mobile community rather than just a transportation service.

The impact? Complaints about his route dropped to near zero. Passengers specifically requested his bus. His supervisors noted that the atmosphere on his route differed markedly from others serving the same area.

Brown’s story illustrates that emotional intelligence isn’t reserved for executives or therapists. It transforms any role where human interaction occurs—which is essentially every role. Whether you’re a teacher, salesperson, healthcare provider, or customer service representative, your emotional intelligence directly determines the quality of experiences you create.

This principle extends powerfully into personal relationships as well. Learn how EQ strengthens intimate partnerships in our guide on emotional intelligence in marriage.

EI is Learnable: What Neuroscience Tells Us

The most empowering truth about emotional intelligence is this: it’s not a fixed trait you either have or don’t have. It’s a set of skills you can systematically develop at any point in your life.

Neuroplasticity: The Biological Foundation for Changing Emotional Habits

For most of the 20th century, scientists believed the adult brain was essentially fixed—that neural pathways were set by adolescence and couldn’t fundamentally change. This belief made emotional intelligence seem like destiny: either you learned these skills in childhood, or you were stuck.

Neuroscience research over the past few decades has shattered this assumption. The brain possesses remarkable neuroplasticity—the ability to form new neural connections, strengthen existing ones, and even generate new neurons throughout life in response to experience.

Here’s what this means practically: every time you practice a new behavior, you’re literally reshaping your brain’s physical structure. Initially, the new behavior feels awkward and requires conscious effort (like learning to drive). With repeated practice, the neural pathways strengthen, and the behavior becomes increasingly automatic (like driving becomes after years of practice).

Daniel Goleman’s “Crossed Arms” Analogy

Goleman uses a simple but powerful metaphor to explain the discomfort of changing emotional habits: crossing your arms. Right now, cross your arms in your natural way. Notice which arm is on top. Now cross them the opposite way. Feels weird, right? Uncomfortable, unnatural, wrong.

That awkwardness is exactly what you experience when trying to adopt a new emotional response pattern. If your habitual reaction to criticism is defensiveness, trying to respond with curiosity instead will feel deeply unnatural initially—just like crossing your arms the “wrong” way.

But here’s the crucial insight: if you kept crossing your arms the new way for three weeks, it would start feeling normal. The same applies to emotional habits. The discomfort isn’t a sign that change is wrong or that you’re not cut out for it—it’s a sign that you’re successfully creating new neural pathways. The awkwardness is evidence of progress, not failure.

The implication is profound: you’re not stuck with your current emotional patterns. Yes, change requires sustained effort and will feel uncomfortable initially. But with consistent practice, new responses become genuinely automatic. You can rewire your brain to respond to stress, conflict, or disappointment in fundamentally different ways.

The 1-2-3 KCG Process: Questions to Guide Intentional Action

How do you actually leverage neuroplasticity to develop emotional intelligence? The Six Seconds framework offers a practical process based on three simple questions that guide intentional action:

Question 1: “What am I feeling?” (Know Yourself) This activates self-awareness. Instead of being unconsciously driven by emotions, you create space for recognition. Pause. Notice the physical sensations. Name the emotion specifically—not just “bad” but “disappointed” or “anxious” or “resentful.”

Question 2: “What do I want?” (Choose Yourself) This activates intentionality. What outcome do I actually want here? What matters most in this situation? This question interrupts automatic reactions and opens the space for conscious choice aligned with your values and goals.

Question 3: “How can I best respond?” (Give Yourself) This activates strategic action. Given what I’m feeling and what I want, what’s my wisest move? This considers both your needs and others’, and connects your choice to the larger purpose.

These three questions—which take seconds to ask yourself—transform emotional reactivity into emotional intelligence. They create the neural groove for new patterns.

Want a structured approach to developing these skills? Explore our comprehensive collection of emotional intelligence exercises with specific practices for each competency.

Practical Guide: The 3 Essential Steps to Increase Your Emotional Intelligence

Theory provides the map; practice creates the territory. Here’s your actionable roadmap for systematically developing emotional intelligence, organized around the three foundational capacities.

Step 1: Build Self-Awareness (Identify and Name)

Self-awareness isn’t about endless introspection or self-absorption. It’s about developing accurate perception of your internal states and patterns.

Why It Matters: You cannot manage what you cannot perceive. Without self-awareness, emotions drive your behavior unconsciously. You react without understanding why, repeat dysfunctional patterns without recognizing them, and remain blind to your impact on others.

Core Practice: Expand Your Emotional Vocabulary

Most people have remarkably limited emotional vocabularies. Ask how they’re feeling and they respond with “good,” “bad,” “fine,” or “stressed.” This imprecision creates imprecision in perception.

Emotions aren’t just positive or negative—they contain specific information. “Anxious” differs fundamentally from “overwhelmed” or “fearful,” even though all might be labeled “bad.” “Content” differs from “excited” or “proud,” though all are “good.”

Action Steps:

- Use precise language: When you notice an emotion, challenge yourself to identify it specifically. Not just “upset” but “disappointed” or “betrayed” or “frustrated.”

- Learn the emotion wheel: Familiarize yourself with tools like the Emotion Wheel that show the full spectrum of human feelings. Aim to use at least 30-40 distinct emotion words regularly.

- Track patterns: Keep a brief emotion log for two weeks. Note what you felt, when, and what triggered it. Patterns will emerge—recurring triggers, habitual reactions, predictable emotional cycles.

Supplementary Practice: Mindfulness Meditation

Mindfulness—non-judgmental attention to present-moment experience—is perhaps the single most powerful self-awareness tool. Even 10 minutes daily creates measurable changes in brain regions associated with emotional regulation.

Start simple: Focus on your breath. When thoughts or feelings arise (and they will), simply notice them without getting caught up in their content. “There’s anxiety. There’s planning. There’s self-criticism.” This creates the observer perspective—the part of you that can witness emotions without being controlled by them.

For specific practices that integrate mindfulness with EI development, see our guide on mindfulness exercises for emotional intelligence.

Step 2: Reflect Before Acting (Improve Self-Management)

Self-management is about expanding the gap between impulse and action—creating choice where automatic reaction once lived.

Why It Matters: Most career-limiting moves and relationship damage occur in moments of poor self-regulation. You send the angry email. You make the sarcastic comment in the meeting. You withdraw when you should engage. These reactions happen so quickly they feel inevitable, but they’re not—they’re simply habits.

Core Practice: The Pause Technique

The most fundamental self-management skill is extraordinarily simple: pause. Before responding to a trigger, create a deliberate space—even if it’s just taking three deep breaths or counting to ten.

This isn’t about suppression. You’re not denying your feelings. You’re creating the neural space for your prefrontal cortex (the planning, rational part of your brain) to come online before your amygdala (the reactive, emotional part) hijacks your behavior.

Action Steps:

- Identify your triggers: What situations predictably cause you to react poorly? A particular type of criticism? Feeling dismissed? Time pressure? Name them explicitly.

- Create if-then plans: “If I feel criticized in a meeting, then I will take three deep breaths before responding.” Pre-commitment dramatically increases your ability to execute in the moment.

- Practice the 24-hour rule for high-stakes communication: When you feel a strong urge to send an emotionally charged email or text, write it—but wait 24 hours before sending. You’ll often decide to either not send it or substantially revise it.

Critical Practice: Seek Radical Feedback

Here’s an uncomfortable truth: you are likely blind to many of your emotional patterns. We all have blind spots—ways we impact others that we simply don’t see.

The antidote is 360-degree feedback: systematically asking people who interact with you in different contexts (managers, peers, direct reports, friends, family) for honest input about your emotional strengths and weaknesses.

Action Steps:

- Ask specific questions: Not “How am I doing?” but “What’s one thing I do that diminishes my effectiveness?” or “When do you see me at my best emotionally, and when do you see me struggle?”

- Make it safe to be honest: People need explicit permission and assurance they won’t face consequences for candor. Consider using anonymous surveys for organizational contexts.

- Listen without defending: The hardest part. When you hear difficult feedback, your instinct will be to explain, justify, or argue. Don’t. Just listen, thank them, and reflect on what they’ve shared.

For a systematic approach to developing this capacity, read our guide on how to increase emotional intelligence with month-by-month practices.

Step 3: Attune and Influence (Improve Social Awareness and Relationship Management)

The final step is taking your emotional intelligence outward—using your awareness and regulation to better understand and influence others.

Why It Matters: No one succeeds alone. Your ability to read others accurately, make them feel understood, and navigate the social world effectively determines your leadership impact, relationship quality, and ultimately your happiness.

Core Practice: Active Listening Beyond Words

Most people don’t really listen—they wait for their turn to talk while formulating their response. Active listening means fully attending to what someone is communicating, both verbally and nonverbally.

Action Steps:

- Focus completely: When someone is speaking, give them full attention. Put down your phone. Turn away from your computer. Make eye contact.

- Notice the full message: Pay attention to body language, vocal tone, energy level, and what’s not being said. Often the real message is in the subtext.

- Reflect back: Periodically paraphrase what you’re hearing: “So what I’m hearing is…” This both confirms your understanding and makes the other person feel genuinely heard.

- Ask about emotions: “How did that make you feel?” or “What’s that experience been like for you?” signals that you care about their emotional reality, not just facts.

Understanding body language and nonverbal cues is crucial for social awareness. Dive deeper with our guide on body language and emotional intelligence.

Surprising Practice: Read Complex Fiction

Research shows that reading literary fiction (as opposed to genre fiction or nonfiction) significantly improves “theory of mind”—the ability to understand that others have mental states different from your own and to infer what those states might be.

Why? Complex literary fiction forces you to navigate ambiguous social situations, interpret subtle emotional cues, and understand characters with radically different perspectives from yours. It’s essentially empathy training.

Action Steps:

- Choose character-driven literary fiction: Works by authors like Toni Morrison, Kazuo Ishiguro, or Ian McEwan that delve deeply into characters’ inner lives.

- Read actively: Don’t just consume the plot. Pause to consider: What is this character feeling? What do they want? Why are they reacting this way? How do they see the situation differently than others?

- Discuss with others: Book clubs or reading discussions expose you to interpretations different from your own, further expanding your perspective-taking ability.

Essential Practice: Improve Your Social Skills Systematically

Social skills—the ability to interact effectively with others—are the visible manifestation of emotional intelligence. They include communication, influence, conflict management, teamwork, and building rapport.

These aren’t innate gifts; they’re learnable competencies. Our comprehensive guide on how to improve social skills for adults provides specific techniques for common challenges like small talk, assertiveness, and reading social situations.

Technology Support: If you’re looking for structured support, consider using apps designed for emotional intelligence development. We’ve reviewed the options in our guide to the best emotional intelligence apps.

The Other Side of the Coin: Critiques and the Dark Side of EI

No comprehensive guide to emotional intelligence is complete without addressing its limitations, controversies, and potential for misuse. Critical thinking requires engaging with countervailing evidence and perspectives.

EI as a Manipulation Tool: When High EQ Becomes a Weapon

Here’s an uncomfortable truth: emotional intelligence is a morally neutral competency. The ability to read emotions accurately and influence them strategically can serve benevolent purposes (helping someone feel understood) or manipulative ones (exploiting vulnerabilities for personal gain).

Research by organizational psychologist Adam Grant and others reveals that individuals with high emotional intelligence can use these skills for dark purposes:

- Machiavellian tactics: High-EQ individuals can be particularly effective at organizational politics—reading power dynamics, building strategic alliances, and undermining rivals while maintaining a likeable facade.

- Deceptive impression management: People skilled at reading emotions know exactly what others want to see and can convincingly fake appropriate responses.

- Emotional exploitation: High social awareness reveals others’ emotional buttons; unethical individuals can push those buttons to manipulate behavior.

The most troubling examples appear in toxic leadership. Charismatic leaders with high emotional intelligence can inspire intense loyalty while pursuing destructive agendas. They read what followers need emotionally and provide it, creating cult-like devotion. History offers sobering examples of emotionally intelligent leaders who used those skills to devastating effect.

The Critical Distinction: This isn’t an argument against emotional intelligence—it’s an argument that EI must be paired with ethical values and good character. Emotional skills without moral grounding are merely tools for exploitation. This is why the most thoughtful EI frameworks, like Six Seconds’ model, explicitly include “pursuing noble goals” as a core component.

Emotional intelligence isn’t about being nice or empathetic—those are applications of EI, not EI itself. At its core, emotional intelligence is about effectiveness in reading and influencing emotional states. How you use that effectiveness is a separate question of ethics and values.

The Validity Debate: Overlap with IQ and Personality (Big Five)

From an academic psychometric perspective, emotional intelligence faces significant criticism regarding its validity as a distinct construct.

The Overlap Problem: Research consistently shows that measures of emotional intelligence correlate substantially with:

- Cognitive intelligence (IQ): Particularly verbal intelligence and abstract reasoning

- Personality traits: Especially emotional stability (low neuroticism), extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness from the Big Five personality model

Critics argue that when you account for IQ and personality, emotional intelligence doesn’t add significant predictive power for life outcomes. The assertion is that EI is essentially a repackaging of already-established psychological constructs rather than a genuinely new form of intelligence.

The Measurement Challenge: The three different EI models (ability, mixed, trait) measure substantially different things:

- Ability tests (like MSCEIT) test performance on emotional tasks, similar to IQ tests

- Mixed model assessments (like Goleman’s ESCI) combine abilities with personality traits and social skills

- Trait measures (like the TEIQue) assess self-perceived emotional competencies, more like personality tests

These different approaches show only modest correlations with each other, raising questions: If they’re all measuring “emotional intelligence,” shouldn’t they align more closely?

The Response: Defenders of EI acknowledge overlap but argue that even if EI shares variance with IQ and personality, it still captures something meaningful. Empathy may correlate with agreeableness, but measuring and training it specifically provides practical value. The framework gives people language and direction for development.

Moreover, the predictive validity debate focuses on whether EI predicts outcomes beyond IQ and personality. But for practitioners, that’s not necessarily the relevant question. The question is: Does the EI framework help people develop skills that improve their lives? And on that pragmatic measure, the evidence is much stronger.

Want to explore this debate more deeply? Our article on emotional intelligence vs IQ examines the complementary nature of these different forms of intelligence.

Social Desirability Bias: The Urge to “Appear” Emotionally Intelligent

A practical problem with emotional intelligence assessment—particularly self-report measures—is social desirability bias: people’s tendency to present themselves in a favorable light.

Questions like “Do you consider other people’s feelings?” or “Can you stay calm under pressure?” are transparently about desirable qualities. Most people will rate themselves higher than their actual behavior would warrant because:

- Self-deception: We genuinely believe we’re more emotionally intelligent than we are (the vast majority of people rate themselves above average)

- Impression management: We want to look good, even on anonymous surveys

- Contextual variation: We think of our behavior in ideal circumstances, not typical ones

This makes self-report EI measures particularly vulnerable to distortion. Someone could score high on an EI questionnaire while behaving in emotionally unintelligent ways in actual situations.

The Solution: This is why ability-based measures (like MSCEIT) or 360-degree assessments (where others rate you) provide more valid data than self-assessment. If you’re serious about gauging your emotional intelligence, don’t rely solely on self-report—get input from others who interact with you regularly.

Despite these limitations, self-assessment can still have value for development purposes (identifying areas to focus on) even if it’s not ideal for accurate measurement.

Vital Applications of EI in Life and Society

Emotional intelligence isn’t an abstract academic concept—it’s a practical framework that transforms how people navigate specific life challenges. Let’s examine several critical applications.

EI and Combating Bullying/Cybervictimization

Research reveals that emotional intelligence serves as a protective factor against both perpetrating and experiencing bullying. Here’s how:

For potential targets: Adolescents with higher EI are less likely to become victims of bullying or cyberbullying. Why? They’re better at:

- Reading early warning signs of social aggression and extracting themselves from risky situations

- Regulating emotional responses to provocations (not giving bullies the reaction they seek)

- Building strong social networks that provide protection and support

- Seeking help appropriately when needed rather than suffering silently

For potential perpetrators: Lower emotional intelligence, particularly deficits in empathy and impulse control, strongly predicts bullying behavior. EI interventions that build empathy and self-regulation show promise in reducing aggressive behavior.

For bystanders: Emotional intelligence empowers bystanders to intervene safely and effectively rather than remaining passive witnesses. They’re better at reading when intervention is needed and how to de-escalate situations.

Schools implementing social-emotional learning (SEL) programs that systematically teach EI skills show measurable decreases in bullying incidents and improvements in school climate.

EI, Health, and Addiction Recovery: The Role of Self-Awareness in Treatment

The connection between emotional intelligence and physical/mental health is profound and bidirectional. Lower emotional intelligence correlates with higher rates of anxiety, depression, substance abuse, and even physical health problems.

The Stress Connection: People with low EI experience more frequent and intense stress responses to daily challenges. They perceive more situations as threatening, regulate stress hormones less effectively, and recover more slowly from stressful events. Chronic stress, in turn, damages virtually every bodily system—cardiovascular, immune, digestive, and neurological.

Addiction and Self-Medication: Substance abuse often represents failed emotional regulation. People use alcohol, drugs, or other addictive behaviors to manage emotions they don’t know how to process. They’re essentially outsourcing emotional regulation to external substances.

Recovery programs increasingly recognize that teaching emotional intelligence skills is crucial for lasting sobriety. Individuals need to:

- Recognize emotional triggers that precede relapse

- Develop healthy coping strategies for difficult emotions

- Rebuild relationships damaged by addiction

- Process shame, guilt, and trauma without numbing

Programs incorporating EI training show significantly better long-term recovery outcomes than those focused solely on abstinence.

Prevention: On the prevention side, adolescents with higher emotional intelligence are substantially less likely to engage in substance abuse in the first place. They possess the self-awareness to recognize when they’re using substances to escape emotions and the self-regulation to choose healthier coping strategies.

EI in Family Context and Parenting

Perhaps nowhere is emotional intelligence more consequential than in families and parenting. The emotional climate parents create shapes children’s developing brains and establishes patterns that last a lifetime.

Emotionally Intelligent Parenting:

- Emotion coaching: Parents who validate children’s feelings while helping them understand and manage emotions raise children with higher emotional intelligence. This looks like: “I can see you’re really frustrated that you can’t watch more TV. It’s okay to feel disappointed. Let’s talk about what you can do with that feeling.”

- Modeling regulation: Children learn emotional management primarily through observation. When parents handle stress, disappointment, and conflict with self-regulation and empathy, children internalize those patterns.

- Secure attachment: Emotionally intelligent parenting creates secure attachment—children’s confidence that their emotional needs will be recognized and responded to. Secure attachment is one of the strongest predictors of lifelong wellbeing.

Relationship Quality: In adult romantic relationships, emotional intelligence predicts relationship satisfaction, stability, and constructive conflict resolution. Partners with higher EI are better at:

- Expressing needs and feelings clearly without blame

- Understanding their partner’s emotional world

- Repairing conflicts before they cause lasting damage

- Maintaining connection during stressful periods

Our detailed guide on emotional intelligence in marriage explores specific applications for intimate partnerships.

Building an EI Culture at Work: The Role of Norms and Heroes

Individual emotional intelligence matters, but organizational culture determines whether those skills flourish or atrophy. Companies serious about emotional intelligence don’t just train individuals—they build cultures that reward and reinforce emotionally intelligent behavior.

Creating EI Norms:

- Psychological safety: Google’s Project Aristotle research identified psychological safety—the belief that you won’t be punished or humiliated for speaking up—as the single most important factor in high-performing teams. This requires leaders who respond non-defensively to challenge and create space for dissent.

- Explicit emotion discussion: Organizations with strong EI cultures normalize talking about emotions at work rather than pretending they don’t exist. They have vocabulary and practices for addressing emotional dynamics explicitly.

- Feedback culture: Regular, honest, growth-oriented feedback becomes the norm rather than the exception. People expect and welcome input about their impact on others.

Celebrating EI Heroes: The stories organizations tell and the people they promote reveal what they truly value. When companies promote primarily on technical excellence while ignoring emotional intelligence, the message is clear—EI doesn’t really matter here.

Organizations building strong EI cultures deliberately celebrate and promote people who exemplify emotional intelligence, creating visible role models. They tell stories of leaders who handled difficult situations with emotional skill and make clear that this is a path to advancement.

For comprehensive workplace strategies, explore our guide on emotional intelligence in the workplace.

Developing Specific EI Competencies: Targeted Resources

While this guide provides a comprehensive overview, mastering emotional intelligence requires focused work on specific competencies. Here are targeted resources for deepening particular skills:

Strengthen Your Foundation

- Assessment: Start by taking our free emotional intelligence test to identify your current strengths and development areas

- Structured Learning: Explore online emotional intelligence courses for systematic development with expert guidance

- Reading: Dive into the best books on emotional resilience to build the foundation for emotional strength

Master Core Skills

- Self-Regulation: Learn emotional self-regulation techniques for managing difficult emotions effectively

- Empathy: Develop your capacity for understanding others with our guide on how to develop empathy skills

- Social Skills: Improve your interpersonal effectiveness with adult social skills development

- Communication: Master the unspoken language with our guide on body language and emotional intelligence

Apply to Specific Contexts

- Leadership: Develop executive-level EI with our guide for emotional intelligence for leaders

- Conflict: Learn to navigate disagreements productively through emotional intelligence conflict resolution

- Relationships: Strengthen intimate partnerships with emotional intelligence in marriage

- Workplace: Apply EI in professional contexts with emotional intelligence examples in the workplace

Build Resilience

- Language: Expand your emotional expression with 10 powerful synonyms for emotional resilience

- Mindfulness: Integrate present-moment awareness with mindfulness exercises for emotional intelligence

- Practice: Engage in daily development with our collection of emotional intelligence exercises

Go Deeper

- Models: Understand different frameworks with our analysis of Goleman’s emotional intelligence model

- Comparison: See how EI relates to cognitive ability in emotional intelligence vs IQ

- Components: Master each element with our breakdown of the components of emotional intelligence

- Strategy: Create your development roadmap with how to increase emotional intelligence

Technology Support

- Apps: Leverage digital tools with our review of the best emotional intelligence apps

Frequently Asked Questions About Emotional Intelligence

What exactly is emotional intelligence, and how is it different from regular intelligence (IQ)?

Emotional intelligence (EI or EQ) is the ability to recognize, understand, and manage your own emotions while also reading and influencing the emotions of others. Unlike IQ—which measures cognitive abilities like logical reasoning, math skills, and verbal comprehension—EI focuses on how you navigate the emotional and social dimensions of life.

The critical difference is that IQ is largely fixed after adolescence, while emotional intelligence can be developed throughout your entire life. IQ might determine what profession you can enter, but EI typically determines how successful you’ll be once you’re there, especially in roles requiring leadership, collaboration, or interpersonal influence.

Can emotional intelligence really be learned and improved at any age?

Yes, absolutely. This is one of the most empowering findings from neuroscience research. Your brain retains neuroplasticity—the ability to form new neural connections and pathways—throughout life. Every time you practice a new emotional skill, you’re literally reshaping your brain’s structure.

The process requires three elements: intentional practice, repetition over time, and willingness to tolerate initial discomfort (new patterns always feel awkward at first). Most research suggests that measurable improvement in emotional intelligence skills takes 3-6 months of consistent practice, with continued development over years.

Programs successfully teaching emotional intelligence to adults range from corporate leadership development to addiction recovery to relationship counseling—demonstrating that change is possible across diverse populations and contexts.

What are the main components or domains of emotional intelligence?

Different models organize emotional intelligence slightly differently, but the most widely recognized framework (Daniel Goleman’s mixed model) identifies four core domains:

- Self-Awareness – Recognizing your own emotions as they occur and understanding how they affect your thoughts and behavior

- Self-Management – Controlling impulsive feelings, managing distressing emotions, and adapting effectively to changing circumstances

- Social Awareness – Reading others’ emotions accurately, understanding their perspectives, and sensing the emotional currents in groups

- Relationship Management – Influencing, inspiring, and developing others while managing conflict and building strong collaborative relationships

The ability model (Mayer & Salovey) organizes these differently into four branches: perceiving emotions, using emotions to facilitate thinking, understanding emotions, and managing emotions. Both frameworks capture similar core competencies.

Explore each component in detail in our guide on the components of emotional intelligence.

Why is emotional intelligence important for leadership and career success?

Research consistently shows that emotional intelligence distinguishes outstanding leaders from average ones. A landmark study by Goleman found that in leadership positions, roughly 90% of the competencies that separate top performers from average performers are emotional intelligence abilities rather than technical or cognitive skills.

Why does EI matter so much for leadership? Because leadership is fundamentally about influencing how people feel, which drives how they think and act. Leaders with high emotional intelligence excel at:

- Creating psychological safety where teams can innovate and take risks

- Inspiring intrinsic motivation by connecting work to meaning

- Reading team dynamics and intervening before problems escalate

- Navigating complex organizational politics effectively

- Providing feedback that actually changes behavior

- Maintaining composure and clarity during crises

The higher you rise in an organization, the more your success depends on EI rather than technical expertise. You can hire technical knowledge; you can’t hire emotional intelligence as easily.

Learn leadership-specific strategies in our guide on emotional intelligence for leaders.

What are the best techniques or practices for increasing self-awareness and managing emotions?

For building self-awareness:

- Expand emotional vocabulary: Replace vague terms (“bad,” “stressed”) with precise emotion words (“disappointed,” “overwhelmed,” “resentful”)

- Practice mindfulness meditation: Even 10 minutes daily trains the observer perspective—the part of you that can witness emotions without being controlled by them

- Keep an emotion journal: Track what you felt, when, and what triggered it for 2-3 weeks to identify patterns

- Seek 360-degree feedback: Ask people who know you in different contexts for honest input about your emotional patterns

For improving self-management:

- Create the pause: Before responding to triggers, take three deep breaths to activate your prefrontal cortex

- Use if-then planning: “If I feel criticized, then I will pause and ask a clarifying question” (pre-commitment increases follow-through)

- Practice the 24-hour rule: For emotionally charged communications, write them but wait 24 hours before sending

- Identify your triggers: Name specific situations that reliably cause poor reactions, then develop specific strategies for each

For comprehensive practices across all EI domains, explore our collection of emotional intelligence exercises and systematic approach in how to increase emotional intelligence.

Conclusion: Your Emotional Intelligence Development Journey

Emotional intelligence isn’t a destination—it’s a lifelong practice of becoming more aware, more intentional, and more skillful in navigating the emotional landscape of human experience.

The evidence is compelling: EI predicts success in leadership, relationship quality, mental and physical health, career advancement, and overall life satisfaction as much or more than traditional intelligence. Unlike IQ, it’s not fixed—you can systematically develop these competencies at any point in your life.

But knowledge alone changes nothing. Reading this guide is merely the starting point. The question that matters is: What will you practice?

Your Next Steps:

- Assess where you are: Take our free emotional intelligence test to identify your current strengths and priority development areas

- Choose one competency to focus on: Don’t try to work on everything simultaneously. Pick the single area that would create the most impact in your life right now—perhaps self-awareness if you feel reactive, or empathy if relationships feel strained

- Commit to 90 days of daily practice: Select 2-3 specific exercises from our emotional intelligence exercises collection and practice them daily. Consistency matters far more than intensity

- Get feedback and support: Share your development goals with someone who will hold you accountable and provide honest feedback on your progress

- Extend into specific contexts: Once you’ve built foundational skills, apply them to your specific challenges—whether that’s leadership, marriage, workplace conflicts, or other domains

The journey of emotional intelligence development is both humbling and empowering. You’ll discover blind spots you didn’t know you had. You’ll experience the discomfort of changing deeply ingrained patterns. But you’ll also experience the profound satisfaction of showing up more fully in your relationships, leading more effectively, and navigating life’s inevitable challenges with greater wisdom and resilience.

Your emotional intelligence isn’t a fixed trait—it’s a skill set you’re building, one intentional choice at a time. The capacity to understand and work skillfully with emotions—yours and others’—might be the most important set of abilities you can develop in your lifetime.

The question isn’t whether emotional intelligence matters. The question is: How will you develop yours?

Start today. Your future self will thank you.